In the speech to the European Youth in Brussels in March 2014, the then-president Obama, speaking of American-led alliances across the world after World War II said the following:

“And this story of human progress was by no means limited to Europe. Indeed, the ideals that came to define our alliance also inspired movements across the globe… …After the Second World War, people from Africa to India threw off the yoke of colonialism to secure their independence… the iron fist of apartheid was unclenched, and Nelson Mandela emerged upright, proud, from prison to lead a multiracial democracy. Latin American nations rejected dictatorship and built new democracies…

It was a very upbeat image of what American post-World War II foreign policy. But it was as upbeat as it was false. It was even stranger that this fantasy was peddled by Barack Obama, who thanks to the years he lived in Indonesia and through the fate of his step-father, knew how one-sided it was. Vincent Bevins’ book “The Jakarta Method” reminds us of reality. In fact, the allies that helped the US win the Cold War were very different from the ones Obama had in mind. They were a rogue gallery, spanning, from Europe, former German Nazis and their collaborators in Eastern Europe, Franco and Greek colonels, Gladio and the Mafia; in Africa, the apartheid regime, Mobutu and the Katanga gendarmes; death squads and latifundistas in Latin America; extreme Islamists, the Taliban, and oppressive kingdoms in the Greater Middle East; corrupt and effete South Vietnamese regime and killing fields dictatorships in Asia—like the one that emerged in Indonesia after Suharto’s coup, the main topic of Bevins’ book.

They all participated in a worldwide loose alliance pitted against the freedom from colonialism and oppression of the peoples from Asia, Africa and Latin America. The big mistake that the United States made by the 1950s was to regard all movements for the emancipation of the Third World peoples as potential Soviet allies and thus as the enemies of the United States. As Bevins writes, there was absolutely no historical reason for such a policy. The United States herself emerged on the world stage as a country that overthrew British colonial rule. In principle, one would expect that it would support similar aspirations of peoples elsewhere. Further, many of the leaders of the liberation movements had a high regard for the United States, its war against the fascist powers, and its Declaration of Independence (even when they saw through cynical untruths about slavery contained in it): Hi Shi Minh cited it many times, Sukarno, in an effort to please the United States, linked the leaders assembled in Bandung in 1955 to Paul Revere’s ride for freedom.

None of that made any difference to the American policy makers who from Truman onward considered (with a couple exceptions, including the Anglo-French-Israeli attack on Egypt in 1956) all Third World liberation movements as suspect, both internationally (pro-Soviet) and domestically (too leftist). Bevins’ book zeroes in on two extremely important episodes in that struggle against people’s emancipation: Brazil and Indonesia.

The story of Indonesia takes most of the book. When Indonesia finally succeeded in liberating herself from the Dutch, it was led by Sukarno, a genuinely popular leader who assembled a broad anti-imperialist coalition that included everybody from moderate Islamists to Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI). But Sukarno’s anti-imperialist foreign polices, his tiermondisme, and his readiness to have good relation with the Soviet Union and China displeased the United States. Bevins very skillfully shows, on the examples of Brazil and Indonesia, how the US Cold War policies in the Third World were fashioned: they were three-pronged.

The sinews were close relations with national Armies and the top echelons of the officer corps. The local generals had often to be weened away from their own instinctive pro-leftism built during the struggle for national independence. They had to be converted into conservative nationalists friendly to US business and political interests and close to US military and security apparatus. This was accomplished through training in the United States and close Army-to-Army contacts. In some cases like Brazil stimulating rightist and conservative instincts among the Army brass was not difficult. The military already played that role historically—even if Bevins rightly points out to the split that did exist even in Brazil between the junior officers who were close to Goulart and those, higher up, who eventually overthrew him.

The second channel of influence was propaganda and misinformation. Here it was through financing of local media and bribery that the objectives were accomplished. But that influence extended also domestically, that is to the opinion-makers in the United States, whose views were then reflected and reported in the Third World countries. Not the least revealing part of Bevins’ book consists of the quotes from the New York Times, including from such journalistic stalwarts like G. C. Sulzberger and James Reston, using what we call today “the fake news” to support the US-orchestrated overthrow of the Arbenz government in Guatemala in 1954, the 1965 military coup in Brazil, Suharto’s power grab in Indonesia, and anti-Allende coup in Chile in 1973.

The third channel was denial or manipulation of economic support, either through direct aid or access to the World Bank and IMF loans, a topic quite well-known to all students of international relations.

What is interesting in American ideological blindness during the Cold War is that in most cases the leaders overthrown or killed were not even in the broadest sense communists nor beholden to the national communist parties. Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala, João Goulart in Brazil, and Salvador Allende in Chile were social democrats; Castro’s revolution was not communist at all: it is the US implacable opposition that transformed it into such; and Sukarno was an authoritarian left-leaning nationalist.

Modernization theory (and Walt Rostow’s “The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-communist Manifesto”) played an important ideological role justifying the three-pronged approach. In direct opposition to what Obama claimed in 2014, the modernization theory (and the US foreign policy) was utterly uninterested in democracy. In effect, it was antidemocratic. But it held, not unlike its Stalinist counterpart, that the Third World countries needed to develop economically first which they would do best by having US-friendly rightwing (ideally military) regimes and that democratization may be left for the future. With hindsight we know the modernization theory worked in South Korea and Taiwan. It may be even argued that it worked in Brazil to the extent that the return of democracy in Brazil, after a hiatus of 25 years, can be thought to have been helped by strong economic growth the country experienced under the harsh military rule.

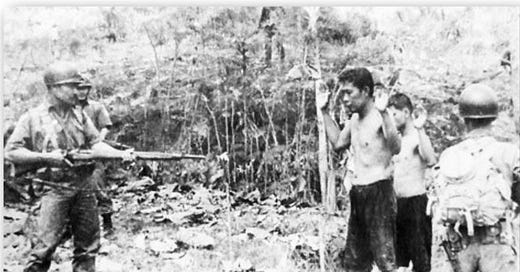

One weakness of Bevins’ otherwise excellent book is his underplaying of domestic reactionary forces in the Third World countries. Again, Brazil and Indonesia are perfect examples. In both, US indeed stimulated the most reactionary forces. But it did not create then. Both coups were largely organized domestically; if one were to give percentages, one could say that 70% of the overthrow was home-grown. Only the rest was foreign-motivated. The Third World was not domestically ideologically homogeneous, nor was everyone likely to benefit from land reforms, broader voting rights (as proposed by Goulart) or by the end of racial discrimination. The extermination orgy (officially termed the “Operation Annihilation”) that enveloped Indonesia after Suharto’s coup was domestically induced while of course US-supported: it led to the killing of about 1 million people, from ordinary workers and students, members of organizations affiliated to KPI, to the rich Chinese (the coup had also an anti-Chinese edge).

Another topic that could have been more elaborated, especially in the case of Indonesia, are all too common mistakes and delusional ambitions of post-independence leaders. Sukarno scrapped elections (in which by the way PKI was doing extremely well, garnering up to 20% of the vote) in favor of nebulous consultation-type of government with himself, of course, as indispensable head. Bevins might have also been more critical of Sukarno’s quasi-imperialist reach for Papua New Guinea, and parts of Borneo that became incorporated into Malaysia. Yes, the British created Malaysia to serve their imperialist interests, but Sukarno’s intentions were not without blemish either.

Finally, I wish Bevins discussed in greater detail the key events surrounding the 1965 Suharto coup. They are, to this day, enveloped in mystery. Was the original left-wing military coup, the trigger for Suharto’s “real deal” coup, a false flag operation or not? What were the objective of the left-wing military in arresting the top generals? Why were they then killed and by whom? What was supposed to have been the next step? It is odd to capture the heads of the various military branches in order to stave off the claimed right-wing coup, and then not to know what to do with them. Or what to do next. Bevins does not want to get involved into the guessing game or counterfactuals, but I think more could have been said even without taking a position one way or another. That crucial turning point is discussed in three pages only.

This is an indispensable book for all those interested in the Third World during the era of the Cold War, and in the links between various operations of “the Anti-Communist International”, a subject whose importance will I think only increase. It might in effect emerge that the decisive global changes were not the ones that we currently see as such (the fall of the Berlin Wall), but rather what happened in countries like China, India, Vietnam, Indonesia, Brazil.